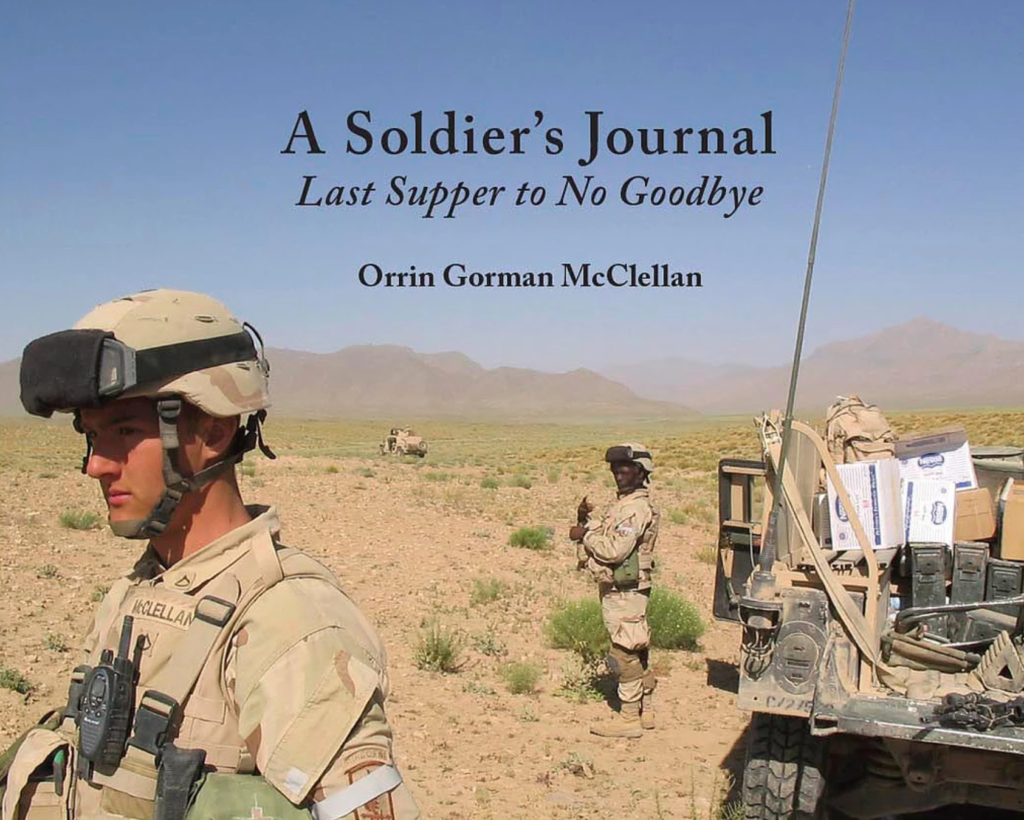

Review of A Soldier’s Journal: Last Supper to No Goodbye

Why is this here? A book review about veterans, combat, and PTSD — on a blog about baseball and sex abuse? It all makes sense if you think about it. The trauma, the stress, the anxiety, depression, even the tragic suicides we see among our returning vets, follow the patterns seen in victims coping and healing from sexual abuse.

A psychologist or a scientist of any training might tell you: The human brain and nervous system form a network like a vast freeway system. A huge, interconnected, fractal-like web takes us wherever we want to go, however we want to get there, with endless choices of routes and where to enter and exit. And a healthy young brain revels, rejoices in the options the road map offers. Ons and offs abound. Freedom awaits.

Orrin Gorman McClellan hit the gas and got on that freeway at age 18, his course clear, his opportunities golden. Ahead lay a stint serving his country. A college degree on the GI Bill. Maybe, if another exit didn’t lure him away, a career as a teacher. Endless branches along that road looked to Orrin like a massive, spreading tree in his future, ripe fruit hanging low from every limb. That was in 2004.

All Photos © Courtesy of publisher. Contact Judith Gorman through

All Photos © Courtesy of publisher. Contact Judith Gorman through

www.asoldiersjournal.org for permission to use.

And We The People sent this hopeful and brilliant young man to Afghanistan. To a place where humanity, compassion and kindness are chucked to the ground if a soldier is to survive. We sent Orrin to a war zone from which thousands of our best and brightest young warriors would not return, and many of those who did make it back would be changed forever.

In less than three years Orrin was home again on Whidbey Island, WA. Gas pedal still on the floor, the other foot slamming periodically on the brake, he hurtled out of control down that broken highway. His road map was destroyed, his off ramps dark and threatening.

While in Afghanistan, Orrin’s journal had become his connection to the reality he had known – his values, his hopes – even as this reality itself slipped away from him. His writings were a frank and revealing portrait of himself, filled with eye-opening awareness, ambivalence, irony, anger, grief, and, from time to time, hope. Once home again, Orrin knew his story needed to be shared. He knew it wasn’t ‘just’ his story. Each day he watched more of his ability to get it done slipping away, yet each day, he felt a growing sense of urgency, of desperation, to complete the task.

Orrin’s freeway turned to a system of dead-end Post Traumatic Stress and Traumatic Brain Injury ruts, steep and terrifying as he descended, unable to ‘down shift.’ He veered into addiction, depression, and anxiety. An arrest, the VA, and counseling could not slow his path. After two years at home, now just 22, he sought help from his parents to get his journal out into the world. To them, from his failing hands, he threw the torch.

His mother and father, Judith Gorman and Perry McClellan, made a pledge to Orrin: they would finish the work that he believed he could not. With encouragement and support from Orrin and other vets, they founded Whidbey Island’s Veterans Resource Center in Freeland, WA, to assist veterans with services, support and community connections. Judith and Perry also accepted Orrin’s challenge of compiling, editing and publishing Orrin’s narrative and photographic journal.

In 2010, Orrin’s road ended when he suddenly and unexpectedly took his own life. Three and one-half years after returning from Afghanistan, he became another victim of the wounds of war.

With Orrin’s death by suicide, Judith Gorman drew strength from her promise to her son and the strong connection she still felt with his presence while compiling, editing and publishing his journal.

Judith tells readers that Orrin may well visit them while they experience his words. She’s right. He came to this reader numerous times through three readings, cover to cover, of his journal.

“This is not just about our son,” she explains. “This could be the experience of anyone’s young son or daughter having gone, too soon, through modern day military training and combat trauma.”

Judith continues, “It’s also been a part of my own grief process: to read and re-read his journals and sort through them all, including his Afghanistan photographs. Through this all I have been given the gift of intimately knowing my son as an adult through the lens of his own literary, articulate, ‘in real time’ journal writing. I’m humbled by his insights and awareness of a complex traumatic experience and his ability to express this while going through it.“

Judith’s pride in her son is abundantly clear. “I’ve been told by many readers that Orrin’s keen awareness of his inner experience, and his articulate forthright descriptions of complex issues, resonate deeply with veteran readers. I was terrified that a veteran might read his words and be triggered to take his or her own life. The feedback I got was exactly the opposite. Some of the sample Reader Reflections, at the end of the book, speak to that. The trauma of the injuries of betrayal by society, combat, disillusionment and loss of self in times of war, is often summed up too easily these days by the letters PTSD and TBI.”

After nine years of that grief, Orrin’s journal was published in October 2018. But Judith is just getting started on her mission. She sees the horrible irony in advocating for veterans when that advocacy shifts into taboo subjects that question the status quo in our military policies and practices at both the pentagon and VA levels of the military and federal government.

“I expect, and actually hope,” Judith says, “those who read Orrin’s Journal will think deeply and feel some waves of stirring up of what has become the status quo of military training and constant combat around the globe and, especially, the impact on our youth—who are our future. Military weapon production and sales in the United States and the support of constant combat around the world has become a part of ‘big business.’ President Dwight Eisenhower warned us, of course, about this, with his ‘military-industrial complex’ speech. I am not a ‘public person’ by nature, but I feel I must step up to the plate now that I know what I know not only to honor Orrin’s spirit, which, of course I still feel, but to honor those many other veterans who have died from or continue to suffer from, their wounds of war, visible and invisible, including death by their own hand. Orrin has, as our children ought to, challenged me as a parent and as a person. He was indeed one of my teachers. I continue to remind myself that meaningful positive change can and does emerge from chaos.”

What meaningful, positive change does Gorman seek, to honor her son’s sacrifice? It’s simple, but groundbreaking all the same. Gorman wants a policy shift at the top of our government, a shift into prevention related to PTSD and combat trauma. Think about that for a minute. She wants us to prevent PTSD and TBI in the first place. How?

Suicide is seen as the problem we need to prevent when, instead, Gorman views suicide as the end result of the actual problem: policies that cause thousands of cases of PTSD and TBI, and the darkness, desperation, and suicide that inevitably follow. How can we prevent the end result, when the root causes already have us flying down that dark highway with no exits?

Based on medical research related to trauma and the not-yet-mature brain and nervous system, Gorman wants the military enlistment age raised to 24. Research shows that the brain and nervous system do not reach fully developed physical maturity until about that age. The same research follows, logically, that the 24-year-old’s fully developed nervous system and brain are not as susceptible as the 18-year-old’s to the trauma damage of battle, or even the damage of battle training.

Then she adds another reason for her suggestion. “24-year-olds also can’t, as easily as 18 year olds, be ‘muscle-memory-trained’ to kill,” Gorman says. She says the pre frontal brain, our judgment, and executive-functioning brain, develops last—between ages 18-24. “Orrin faced this moral injury struggle as a recruit, and it was magnified by the post World War ll military training system changes. He struggled in training with the need to ‘kill to stay alive’ rather than his value of ‘save the world for democracy’ of previous wars. In training, it’s telling that rifle targets aren’t bulls-eyes any longer. They are now shaped like humans. When you do a repetitive action enough times, muscle memory overrides, especially the still not fully developed judgment areas of the brain, making ‘shoot to kill people’ a reflexive pathway reaction, rather than a logically considered ‘executive function’ action.”

Gorman says, in military training, the on ramps and exits, the value judgements about what’s right, the “well… lets think about this” back roads, are eliminated in favor of that well-used, high-speed pathway, that single instinctive action — especially in the not-yet-fully-mature brain and nervous system.

By the end of boot camp, Orrin realized the recruiters had lied to him about the glory of military service. He was angry and bitter about that, but it didn’t change his commitment. His mother says “Orrin was so idealistic he couldn’t believe recruiters would lie. But he told me, ‘I made an agreement and I won’t break my part of it. I can’t do anything about their end of it.’ He told me he wasn’t afraid of dying. He was afraid of losing what he valued about himself.”

Orrin Gorman McClellan held on to those values as long as he could before losing that battle. Reading his journal might well save a life, through a greater understanding of the struggles so many of our returning veterans face.

Blogger’s note: Deepest gratitude is due Judith Gorman for her time and devotion in contributing to this article. Please go to https://www.asoldiersjournal.org/ to see excerpts and to order a copy. If you’re a librarian, college professor, high school teacher, coach or parent, or seeking to learn more about how to assist veterans as they transition home, or if you want more information about Orrin’s Journal, use the contact form on the web site to contact Judith Gorman.