It was just another tweet from a tweeter on the twitter, a quick stop on a casual scroll down the screen. Then I hit the brakes.

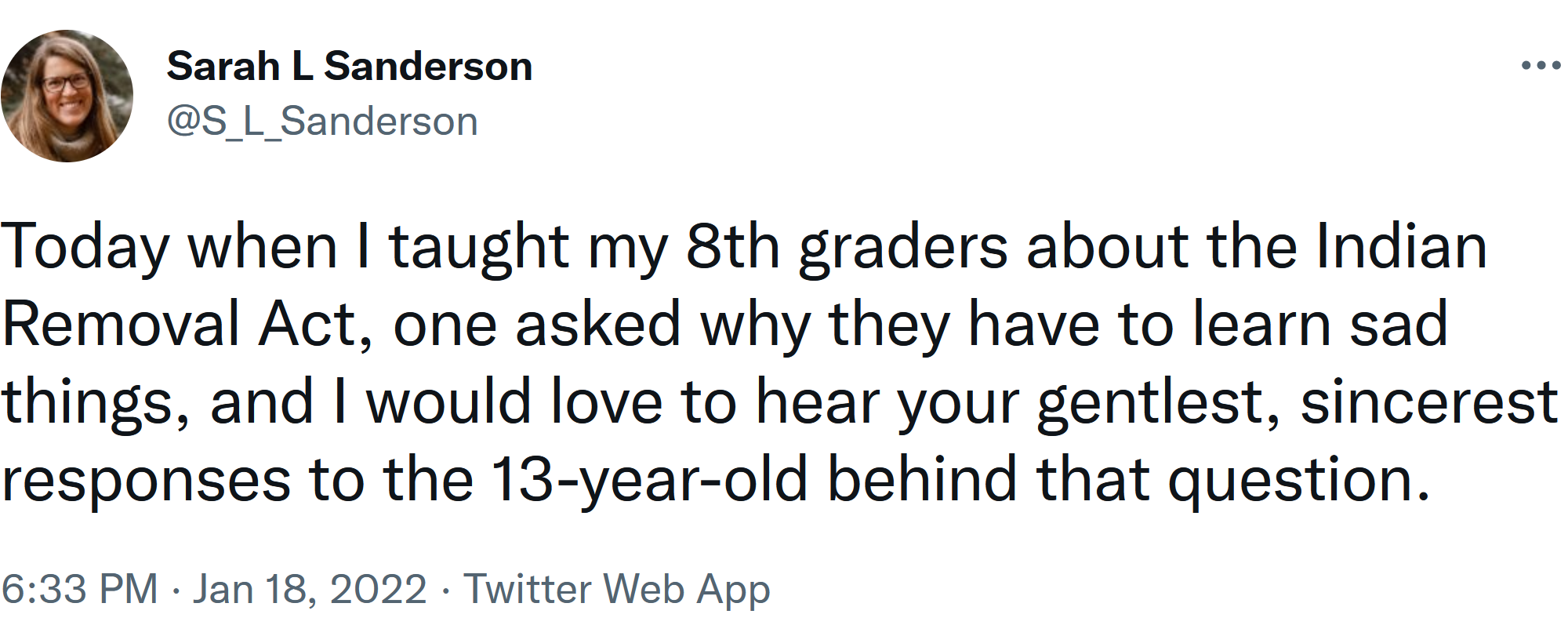

“Today when I taught my 8th graders about the Indian Removal Act,” the tweeter tweeted, “one asked why they have to learn sad things, and I would love to hear your gentlest, sincerest responses to the 13-year-old behind that question.”

As my brain scratched around for suitable 280-character wisdom, I read through the replies. And they were gold.

You can find that tweet, with all the beauty and power in those replies, right there on the twitter:

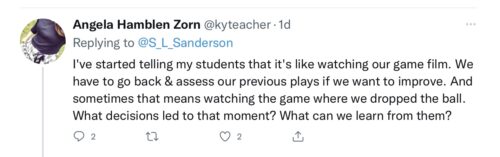

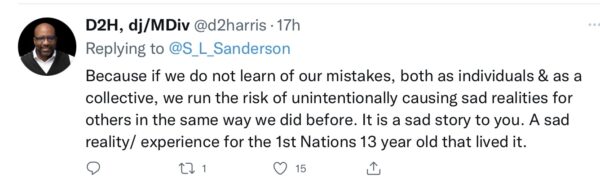

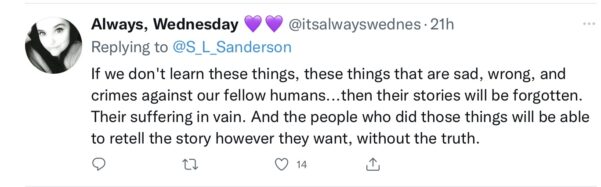

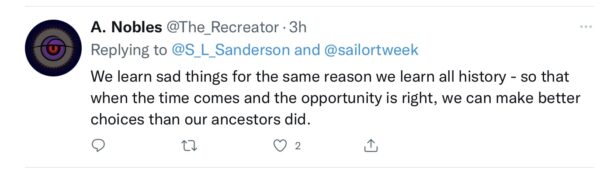

And a tiny sampling of those replies…

Well, yeah. Game film is pretty damn sad sometimes but if we want to do better next week, we watch it. We face the harsh reality of what we did, and we learn to throw that pitch, make that block, finish that drive to the hoop.

That kid you’re reading about lived through it, suffered from it, maybe even died from it, 200 years ago. A 13-year-old student today can surely handle some sadness over that tragedy for an hour between math and gym class.

That kid you’re reading about lived through it, suffered from it, maybe even died from it, 200 years ago. A 13-year-old student today can surely handle some sadness over that tragedy for an hour between math and gym class. Remember the long summer of BLM protests after George Floyd’s murder? …and the people who couldn’t take protests seriously if they got violent? Peace is a strange demand of protesters, when the very thing being protested was murder. Murders. Too many murders to count. Maybe it’s inevitable, if we keep refusing to listen, that the only way we’ll have a real reckoning — the only way we’ll learn the sad things — is widespread violent retribution. Maybe violence begets more violence, and being gentle in response is exactly how to NOT be taken seriously.

Remember the long summer of BLM protests after George Floyd’s murder? …and the people who couldn’t take protests seriously if they got violent? Peace is a strange demand of protesters, when the very thing being protested was murder. Murders. Too many murders to count. Maybe it’s inevitable, if we keep refusing to listen, that the only way we’ll have a real reckoning — the only way we’ll learn the sad things — is widespread violent retribution. Maybe violence begets more violence, and being gentle in response is exactly how to NOT be taken seriously.  Winners do write the history, don’t they? They certainly wrote the American-exceptionalism-without-question indoctrination I was raised on. And they enforced it with wood paddles and bare-hand swats, because, y’know, Freedom. And there are still those who fear the sadness that comes with cracks in that mantle. Our ex-president himself rallied millions of scared, indignant Americans with “get that SOB off the field” because one guy in a helmet and pads wanted us to listen to some sad things.

Winners do write the history, don’t they? They certainly wrote the American-exceptionalism-without-question indoctrination I was raised on. And they enforced it with wood paddles and bare-hand swats, because, y’know, Freedom. And there are still those who fear the sadness that comes with cracks in that mantle. Our ex-president himself rallied millions of scared, indignant Americans with “get that SOB off the field” because one guy in a helmet and pads wanted us to listen to some sad things.  Except we tend to plug our ears and vilify the ones teaching us the sad things. And we keep on making bad choices. A person I dearly love was a lifelong supporter of US action in Vietnam. She attacked and degraded anyone who protested the war or the draft, decades after the war ended. Then came Ken Burns’ 2017 “Vietnam” series. “The government lied to us!” she told me. I said, if it took Ken Burns to convince you, good for him. And good for you. Meanwhile, we’ve waged forty-plus years of unending unwon wars in foreign lands, because we didn’t listen…

Except we tend to plug our ears and vilify the ones teaching us the sad things. And we keep on making bad choices. A person I dearly love was a lifelong supporter of US action in Vietnam. She attacked and degraded anyone who protested the war or the draft, decades after the war ended. Then came Ken Burns’ 2017 “Vietnam” series. “The government lied to us!” she told me. I said, if it took Ken Burns to convince you, good for him. And good for you. Meanwhile, we’ve waged forty-plus years of unending unwon wars in foreign lands, because we didn’t listen… Of course. Trouble is, whether we’re 13 or 30 or a cop or a senator or a 70+-year-old president, we don’t want to hear the sad things, don’t want to know the things that are hard to listen to. Sexual assault survivor and advocate Rachael Denhollander, in a presentation you can watch right here, told the Trinity Forum: “Sometimes it is emotionally easier to not know that data, and all of us have this intrinsic desire to not have to see the darkness that is around and to not have to comprehend that. But there is no greater cowardice than chosen ignorance, and at this point in time the ignorance is nothing but chosen.”

Of course. Trouble is, whether we’re 13 or 30 or a cop or a senator or a 70+-year-old president, we don’t want to hear the sad things, don’t want to know the things that are hard to listen to. Sexual assault survivor and advocate Rachael Denhollander, in a presentation you can watch right here, told the Trinity Forum: “Sometimes it is emotionally easier to not know that data, and all of us have this intrinsic desire to not have to see the darkness that is around and to not have to comprehend that. But there is no greater cowardice than chosen ignorance, and at this point in time the ignorance is nothing but chosen.” Would it be gentle enough to tell a 13-year-old student that chosen ignorance is cowardice, and that’s why we learn the sad things?

Can we magically unburden someone who’s carrying a load of multigenerational trauma? Maybe so, maybe a little bit, maybe not. But certainly the truth – the sad truth we find in listening to those sad stories – is more important than the few minutes trauma we may suffer from hearing it.

This is the teacher I’d want for my kids, for my grandkids, for every kid. A teacher who doesn’t pontificate, but who instead asks his students for the answers, who lets them think for themselves, who guides them to find their own truth.

…and that’s why I love teachers. I love teachers who question, who challenge, who allow students to find the truth that sets them free. When I think of heroes, when I think of those who have served the cause of freedom, my brain does not automatically conjure images of soldiers packing weapons and dodging bullets in foreign lands. My thoughts are with teachers, and I thank them for their service. They have shown us how we got here, as raggedy and imperfect as we may be, and they are our best hope for what is to come.

When Dr. King wrote from the Birmingham jail, he told us why the sad things matter:

“… the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is …the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice. …Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.”

That’s why we learn the sad things.

Important recognition of learning from what we don’t know that we think we know. How can it be WRONG to teach what actually happened–in a balanced way, of course. Thanks for writing this & putting these quotes and reactions together. kjc

Thank you Kay. My favorite thing in writing this was by happenstance hearing Rachael Denhollander’s amazing short talk. I highly recommend it to anyone who has the courage to listen. Her words “there is no greater cowardice than chosen ignorance” struck right at the heart of why we have to learn the sad things, and to flip her words around, we should validate the sadness we feel when we learn those things, and celebrate the courage it takes to learn them anyway. – Bill